Digital Grotesque II (2017)

Digital Grotesque II, a full-scale 3D-printed grotto, premiered at the Centre Pompidou's Imprimer le monde exhibition and is part of the museum's permanent collection. This installation challenges conventional paradigms of design by exploring a novel collaboration between designer and computational system.

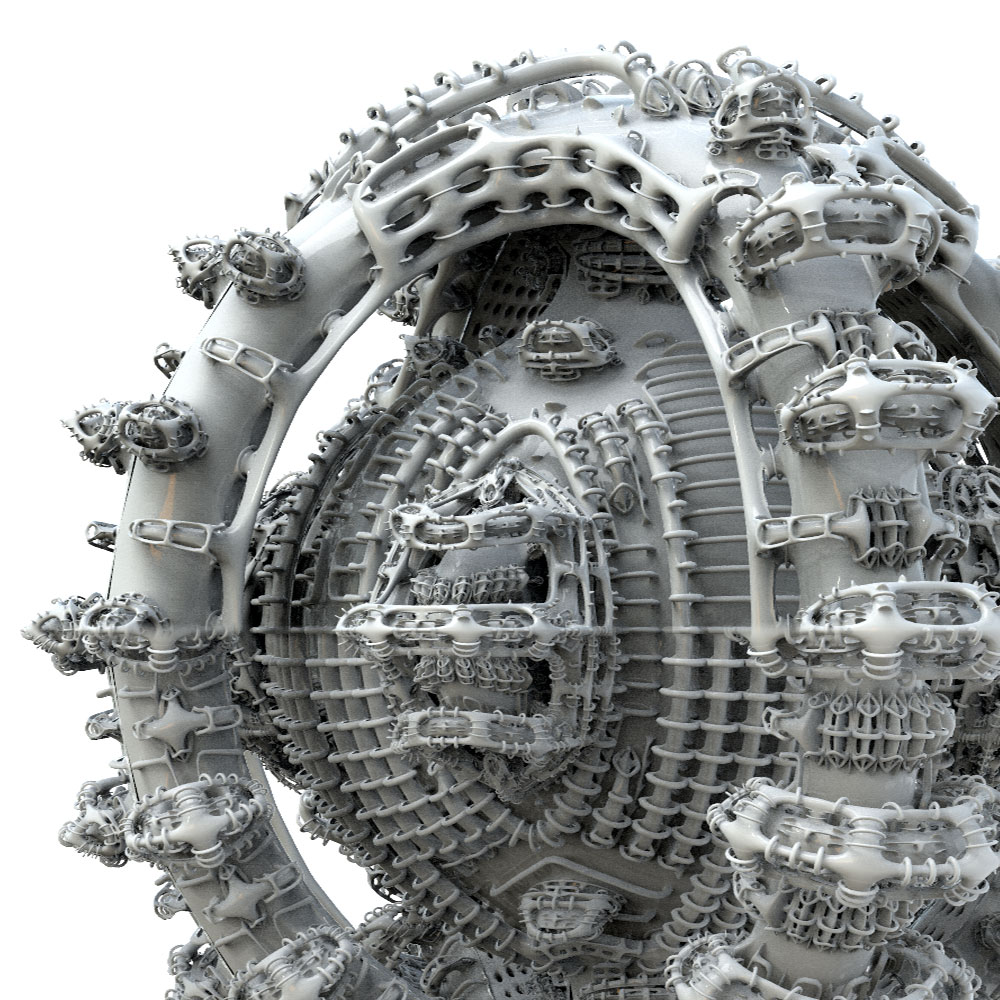

Here, the computer transcends its role as a passive instrument, becoming an active, generative partner capable of expanding the designer's imaginative and formal capacities. From an initial digital seed, the system generated millions of intricate branches, recursively growing and folding to compress hundreds of square meters of surface into a 3.5-meter-high, seven-ton 3D-printed sandstone structure.

The resulting architecture presents a complex, rich formal language that is simultaneously disorienting, intriguing, and evocative, yet deliberately non-prescriptive. It inhabits a space between the man-made and the natural, between order and chaos, offering unexpected moments of surprise.

Beyond Traditional Design Tools

Digital fabrication has fundamentally changed what we can build, yet design tools remain constrained by what humans can directly represent and imagine. Digital Grotesque II demonstrates a different approach: the computer as an active creative partner capable of generating forms that are undrawable and unimaginable by human designers alone.

Evolving Autonomy: From Generation to Evaluation

This project marks a significant evolution from its predecessor, Digital Grotesque I . In the first iteration, the computational system primarily served as a form generator, with the architect consistently evaluating each proposal, adjusting parameters, and synthesizing forms into new iterations. This workflow, while productive, still mandated continuous human oversight and decisive intervention at every stage of the design process.

Digital Grotesque II advances this human-computer collaboration by endowing the computational system with not only generative capacity but also evaluative autonomy. Rather than merely producing options for human assessment, the system learns to evaluate its own creations and optimize them accordingly. This represents a profound progression: from the computer as a sophisticated form generator to a more autonomous designer, capable of iterative self-improvement.

Question of Purpose: Optimizing a Grotto

Yet this enhanced autonomy immediately raises a fundamental question: if the computer can now optimize designs through iterative learning, what should it optimize toward? Unlike conventional architectural structures with clear functional requirements - maximizing structural efficiency, minimizing material use, or optimizing environmental performance - a grotto serves no explicit functional purpose. Its value lies entirely in the experience it creates for those who encounter it. This absence of conventional optimization targets opens space for a different kind of architectural intelligence.

Quantifying Ephemeral Criteria

Digital Grotesque II addresses the challenge of optimizing for non-functional criteria by attempting to quantify what might be called "soft criteria" — elusive design factors that influence emotional and perceptual responses, yet resist traditional metric-based measurement. These soft criteria, such as aesthetic values, are highly relevant to how humans interact with the built environment, as they directly influence the emotions people experience through architecture. We can distinguish between various types of emotions, including aesthetic emotions (like being moved, fascination, and awe), epistemic emotions (such as curiosity, interest, and insight), and others related to amusement, humor, joy, energy, or relaxation.

Geometric Properties for Engagement

Rather than claiming to directly measure aesthetic experience itself, the project identifies three geometric properties that demonstrate positive correlation with viewer engagement and interest:

- Experience-ability: changes in the form’s appearance or visibility through a shift of the viewer’s position or perspective.

- Compressibility: the degree of geometric information that cannot be simplified through symmetry groups and repetition.

- Depth-complexity: measuring the topological alternation between void and solid within a structure, cultivating an immersive experience

These metrics enabled the computer to learn relationships between geometric properties and human response. Through evaluation of design variations by online volunteers, the system developed predictive models linking form and geometric properties to emotional impact. The computer could then generate and iteratively optimize proposals specifically to maximize curiosity and sustained engagement.

Evolving Role for the Architect

In this process, the architect's role transforms from direct designer to curator - steering the computational exploration, evaluating proposals, and synthesizing the most compelling solutions into a singular form. The human provides aesthetic judgment and contextual understanding while the computer provides generative capacity that far exceeds individual imagination.

However, this approach raises important questions about the nature of aesthetic experience itself. The reduction of human response to quantifiable metrics, while enabling computational optimization, necessarily simplifies the complex cultural, symbolic, and personal dimensions through which architecture creates meaning. The challenge lies in harnessing computational creativity while preserving the deeper human values that make architecture culturally significant.

An Imaginary Space

Digital Grotesque II demonstrates how computational design can transcend human imagination while remaining deeply engaged with human perception. Standing before the grotto, one encounters a previously unseen richness of detail — a visual and spatial complexity that seems to exceed direct human conception, yet clearly responds to human sensibilities. The architecture is at once disorientating, intriguing, and evocative without being prescriptive. Digital Grotesque is a testament to and a celebration of a new kind of architecture that leaves behind traditional paradigms of rationalization and standardization and instead emphasizes the viewer’s perception - evoking marvel, curiosity and bewilderment.

Though generated through autonomous computational processes, the form evokes analogies across multiple domains - from architectural traditions to natural formations. This suggests that the computer, while creating the unprecedented, may have inadvertently uncovered patterns that resonate with deeper human perceptual structures and archetypes. It raises the question about the ultimate origin of the form.

Digital Grotesque II offers a glimpse into the ongoing evolution of computational design, prompting us to consider the emergence of machines that can assess and refine their own creations based on aesthetic criteria.

Implications for the Future of Design

As computational systems can now not only generate forms but also evaluate and optimize them by identifying statistical patterns in human preferences, fundamental questions arise about the very nature of design intelligence itself. Does this process lead to the discovery of genuinely novel aesthetic principles, or does it primarily optimize for the reproduction and amplification of existing human biases and preferences? How might we encourage truly emergent 'discoveries' from such systems?

This trajectory toward autonomous computational evaluation suggests implications for the future of design practice. As machines become capable of independent aesthetic judgment, the designer's role may continue to evolve from direct creator to something more akin to a teacher or orchestrator - defining learning objectives and evaluating outcomes while allowing computational systems increasing autonomy in the creative process. This could lead to design partnerships where human and machine intelligence operate at entirely different scales of imagination and evaluation, potentially unlocking creative territories that neither could access alone.

Digital Grotesque II in Figures

Virtual:

- 16,386 design variations

- 260 million individual surfaces

- 42 billion voxels

- 156 GB production data

- Calculated on ETH EULER high-performance cluster (2000 GB Ram)

Physical:

- Sand-printed elements (silicate+binder)

- 3.45 meters height

- 537 m2 total surface area

- 7 metric tons weight

- 280 µm layer resolution

- 4.0 x 2.0 x 1.0 meter maximum print space

Design Development: Printing: Assembly: |

2 years 1 month 2 days |

Team

| Fabrication and assembly: |

Michael Thomas Philippe Steiner Allegra Stucki Florentin Duelli Jan Francisco Anduaga Katharina Wepler Lorenz Brunnner Nicolas Harter Dominik Keller Max Spett Alexander Canario |

|

| Digital support: |

Matthias Leschok Alvaro Lopez |

|

| Photos: | Fabrice Dall'Anese Michael Lyrenmann Demetris Shammas Jann Erhard Hyunchul Kwon |

|

| Video: | Kaufmann & Gehring | |

Partners and Sponsors

| Chair for Digital Building Technologies, ETH Zurich | |

| Department of Architecture, ETH Zurich | |

| Centre Pompidou | |

| Christenguss AG | |

| Bosshard + Co. AG | |

| Suter Elektro AG |

The geometry was calculated on the Euler High-Performance Computing Cluster at ETH Zurich. Components were printed on ExOne printers by Christenguss AG.